Companies around the world use many different types of sheet metal to produce their products. When designers and engineers are trying to decide which material to use to meet the desired attributes for their product, they are considering many different characteristics, or mechanical properties.

These mechanical properties are critical because they determine how a material will perform under different conditions, such as during manufacturing, assembly, or final use. Each property tells part of the story—whether it’s how much a material can bend before breaking, how much load it can carry without deforming, or how resistant it is to wear or cracking over time. Selecting the wrong material could result in product failure, excessive costs, or manufacturing challenges, while the right choice can lead to a more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective production process. That’s why understanding the mechanical properties of materials is not just helpful—it’s essential to quality manufacturing and product design.

What Are Mechanical Properties of Materials?

Mechanical properties are used to identify and classify materials. They are properties that involve a material’s reaction to an applied load.

In simple terms, mechanical properties define how a material responds when subjected to forces such as tension, compression, bending, or twisting. These properties give engineers and manufacturers valuable insight into how the material will behave during the manufacturing process and in its final application. For example, some materials are chosen because they are strong and can withstand heavy loads, while others are selected for their flexibility or resistance to cracking.

Understanding these properties is particularly important when working with sheet metals, where forming, bending, and stretching are part of the production process. Without a clear knowledge of mechanical properties, product performance could suffer, tooling could wear out faster, and production costs could increase due to unexpected failures or excessive material waste. That’s why mechanical properties are crucial to material selection, process planning, and quality control in manufacturing environments.

What Is the Difference Between Physical & Mechanical Properties of Materials?

While mechanical properties describe how a material responds to applied forces, physical properties are characteristics that do not involve external loads or stresses. Physical properties define the material’s inherent makeup and structure, regardless of how it is used or processed.

Examples of physical properties include:

- Density

- Melting point

- Electrical conductivity

- Thermal conductivity

- Magnetic properties

- Corrosion resistance

These traits help engineers understand how the material will behave in different environments or under specific conditions, such as exposure to heat, electricity, or chemicals.

On the other hand, mechanical properties are directly related to how the material performs when subjected to mechanical forces during forming, shaping, or assembly. These properties are critical in determining formability, durability, and overall part quality.

In manufacturing, both sets of properties play an important role. However, when it comes to stamping, bending, drawing, or other forming operations, understanding the mechanical properties of sheet metal is essential for process optimization and preventing defects like springback, twisting, or cracking.

What Are the Different Mechanical Properties of Materials?

Mechanical properties define how a material responds when subjected to different types of forces or loads. These properties are essential for selecting the right material for the job and for predicting how the material will behave during the forming, stamping, or manufacturing process. Here are some important mechanical properties of materials:

Yield Strength

Yield Strength (YS) is the maximum stress a material can withstand before it starts to deform permanently. Up to this point, the material will return to its original shape when the load is removed. Once the yield point is exceeded, plastic deformation begins.

Tensile Strength

Tensile Strength (TS), sometimes called Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS), is the maximum amount of stress a material can handle while being stretched before it breaks. This value helps define the upper limit of force that can be applied in tension.

Total Elongation

Total Elongation (TE) measures how much a material can stretch before it fractures. This property is usually expressed as a percentage and provides insight into the ductility of the material. A higher elongation means the material is more flexible and less likely to crack during forming.

N-Value (Strain Hardening Exponent)

The N-Value indicates how much a material strengthens as it is plastically deformed. It’s a measure of stretch formability and reflects the material’s ability to distribute strain evenly during forming. Higher N-values help prevent localized thinning.

R-Value (Plastic Strain Ratio)

The R-Value reflects a material’s ability to resist thinning or thickening during deformation. A higher R-value indicates better drawability, making it especially important in deep-drawing operations.

Elastic Modulus (Young’s Modulus)

Elastic Modulus measures the stiffness of a material. It defines the relationship between stress and strain in the elastic (non-permanent) region. A high elastic modulus means the material is stiff and resists elastic deformation.

Poisson’s Ratio

Poisson’s Ratio describes how much a material contracts in width when stretched in length, or expands in width when compressed. This property is important for predicting dimensional changes during forming.

Hardness

Hardness is the material’s resistance to indentation, scratching, or wear. Common hardness tests include Rockwell, Brinell, and Vickers methods. Harder materials generally have higher strength but may be more brittle.

Ductility

Ductility refers to a material’s ability to deform without breaking, usually by stretching or bending. High ductility is crucial for parts that require extensive forming or shaping.

Toughness

Toughness is the material’s ability to absorb energy before fracturing. It is a combination of strength and ductility and is especially important for parts exposed to impact or sudden loads.

Fatigue Strength

Fatigue Strength is the maximum stress a material can withstand for a specified number of cycles without failure. It is critical for components subjected to repeated loading and unloading over time.

Creep Resistance

Creep is the slow, permanent deformation of a material under a constant load over an extended period, typically at elevated temperatures. Creep resistance is essential for materials used in high-heat environments.

Fracture Toughness

Fracture Toughness describes a material’s ability to resist crack propagation. Even materials with high strength can fail suddenly if their fracture toughness is low.

Impact Strength

Impact Strength measures a material’s ability to absorb shock or sudden forces without breaking. This property is tested using methods like the Charpy or Izod impact tests.

Shear Strength

Shear Strength is the maximum stress a material can withstand in a shearing scenario—when forces are applied parallel but in opposite directions. This property is vital in applications where cutting, punching, or shearing operations are involved.

Compressive Strength

Compressive Strength is the ability of a material to resist forces that attempt to reduce its size. It is especially relevant for materials that bear loads in columns, supports, or structures.

Resilience

Resilience is the capacity of a material to absorb energy when it is elastically deformed and to release that energy upon unloading. It represents the material’s ability to spring back without permanent deformation.

Brittleness

Brittleness is the tendency of a material to fracture without significant deformation. Brittle materials have low ductility and can break suddenly under stress.

Formability

Formability refers to the ability of a material to undergo plastic deformation without cracking or failing. This property is especially important in sheet metal applications where materials are bent, stretched, or deep drawn into complex shapes.

Work Hardening

Work hardening, also known as strain hardening, is the increase in strength and hardness of a material due to plastic deformation. As a material is worked (for example, during rolling or forming), it becomes stronger but less ductile.

Wear Resistance

Wear resistance is the material’s ability to withstand gradual surface deterioration from friction, abrasion, or contact with other materials. This is important in high-friction applications or moving components.

Surface Finish Sensitivity

Some materials are more sensitive to surface defects, scratches, or imperfections, which can lead to premature failure or crack initiation under stress. This property is important when surface quality affects fatigue life.

Stiffness-to-Weight Ratio (Specific Modulus)

This property compares stiffness (elastic modulus) to material density. It is particularly important in industries like aerospace or automotive where both lightweight construction and rigidity are required.

Strength-to-Weight Ratio (Specific Strength)

This measures the material’s strength relative to its weight. Materials with a high strength-to-weight ratio are preferred in applications where minimizing mass is critical.

Anisotropy

Anisotropy is the directional dependence of mechanical properties. Some materials have different strengths or elongation characteristics depending on the direction of the load, especially after rolling or forming.

Thermal Expansion Coefficient

Although technically a thermal property, it plays a role in mechanical performance during manufacturing. Materials expand or contract with temperature changes, which can cause warping, dimensional changes, or residual stress buildup in formed parts.

Residual Stress

Residual stress refers to internal stresses that remain in a material after forming or machining. These stresses can affect springback, part distortion, or dimensional stability over time.

Machinability

Machinability describes how easily a material can be cut, drilled, or machined into a finished part. While not always classified strictly as a mechanical property, machinability affects manufacturing efficiency and tool wear.

Why Do These Mechanical Properties Matter?

Each mechanical property provides insight into how a material will behave during forming, shaping, or in-service use. For sheet metal applications, selecting materials with the right combination of strength, ductility, and formability helps reduce scrap, minimize defects like springback, and control manufacturing costs. That’s why a thorough understanding of these properties is essential for engineers, designers, and manufacturers working to produce high-quality stamped parts and assemblies.

The Importance of Understanding Mechanical Properties of Materials

Some parts need strength to withstand forces or pressures, some are light weight to be efficient, but all need to meet the formability requirements of a stable product design. One of the key components to proper selection and process capability is understanding the Sheet Metal’s Mechanical properties. This leads us to two main questions: how can we get those mechanical properties? what does each mechanical property mean?

How to Test Mechanical Properties of Materials

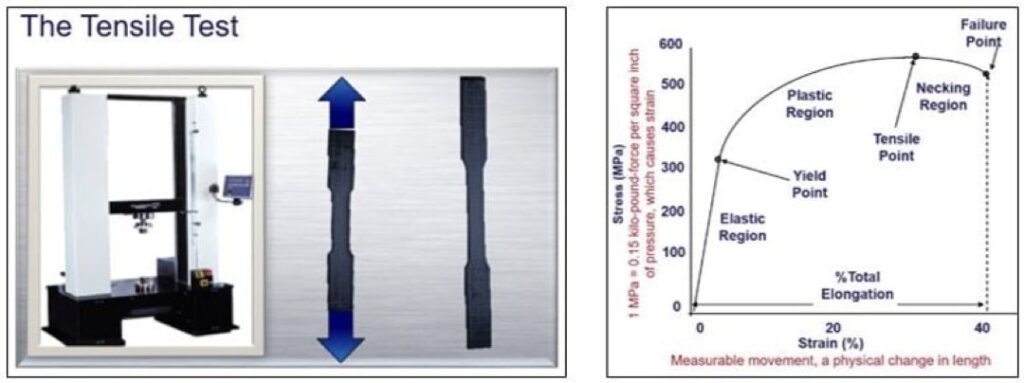

To respond to those questions, let’s start talking about the tensile test. The tensile test is a standardized method to determinate the materials mechanical properties.

This method is performed by holding a sample, called a specimen, in a rigid device and increasing the load or the stress applied to pulling on the sample until failure occurs. During this process, we record how much stress, or pulling force, is being applied to the material and what shape changes are occurring to the specimen. The shape changes we are looking for are length (elongation) and thickness of the material. The output information is plotted in graphical form and is referred to as the stress-strain diagram. Most of the key mechanical properties come from the tensile test.

Mechanical Properties of Materials Determined During the Tensile Test

The most used mechanical properties determined during the tensile test are:

Yield Strength

The YS is a measure of a material’s elasticity. This shows the highest stress that can be applied to a material prior to permanent (plastic) deformation; in other words, it is where the elastic deformation ends, and the plastic deformation begins.

Tensile Strength

The TS is the maximum amount of stress a material incurs prior to failure; it also defines the onset of necking.

Total Elongation

The TE is a percentage by which a material can be stretched before it breaks, usually expressed as a percentage over a fixed gauge. Ductility is often reported as % elongation, which is also a rough indicator of formability (a higher number indicates improved formability).

N-Value

The N-Value is also known as strain hardening exponent; it indicates the relative stretch formability of sheet metals and the increase in strength due to plastic deformation. Measured as the slope of the true stress—strain curve, generally between 10-20% strain. A higher number indicates better ability to reduce concentrated strain by redistributing the strain over a larger area.

R-Value

The R Value, sometimes referred to as the plastic strain ratio, indicates the ability of a sheet metal to resist thinning or thickening. A higher number indicates better drawability.

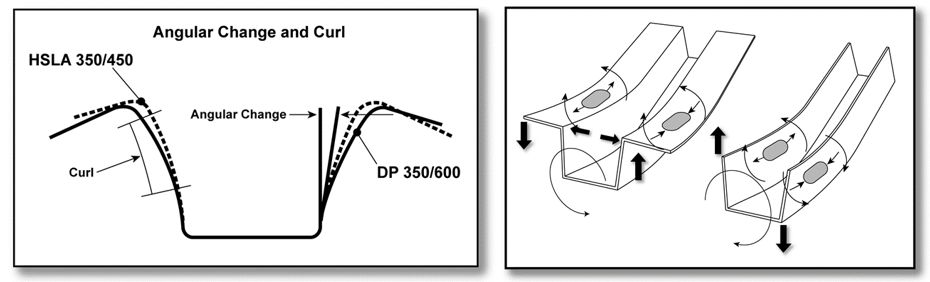

Optimizing Material Performance: Mitigating Springback Challenges

The relaxation of the atomic spacing and residual stress, or springback, in sheet metal causes the stamped part to react in three distinct ways. The part can twist, sidewalls and flanges endure angular changes, and sidewalls can curl. The twisting of the part is due to unbalanced strain pattern either in the sidewall or flange, or in some cases, both. The stresses in the stamping create a torsion effect and the part reacts to the torsion by twisting. Sidewalls and flanges change angularly, typically due to the thickness change that occurs as the metal moves over the forming radius. This thickness reduction coupled with varying strain levels throughout the wall depth creates a tension effect causing the wall and/or flange angle to change. Sidewall curl is a result of an uneven strain gradient that occurs during the bending and straightening of the material as it moves over the draw radius. These strain gradients will be different along the height of the wall, creating a curvature in the stamping.

Die designers compensate the geometry of the die to correct or stabilize the part dimensionally. Some designers add stiffeners down the height of the wall or small stiffener beads in the radius to lock in stresses at a given point of the part geometry. Changes in the forming process will affect the residual stresses in the stamped part and dimensional deviation may accrue. These dimensional changes may not meet quality standard or cause assembly issues further into the joining operations. Changes in lube reapply or blank wash roll pressures will have a dramatic effect on the strain patterns in the stamping. An increase of lube can lessen the amount of plastic deformation in the part resulting in an angular change in the sidewall or even the twist in the stamping. Do not rely on the restrike operation to correct springback changes in the initial forming operation, advanced high strength steel will not react the same as mild steel.

The higher cost of advanced high-strength steel and an undisciplined process can result in large losses due to scrap and rework. Creating a press and die recipe to follow during the stamping operation is highly recommended. Process control is critical to replicating a quality stamping and minimize the losses due to scrap or rework. The recommendations are to perform a formability analysis and dimensional check of the part to identify strain levels and dimensional accuracy. The use of templates to check draw lines and measurements of draw in amounts help monitor consistency of the stampings.

Need Help Understanding Mechanical Properties of Materials? The Phoenix Group Has You Covered!

A good understanding and use of these mechanical properties are very important and beneficial to the manufacturing industry. These mechanical properties will allow engineers to predict failures, behaviors, and tendencies of metals during the forming processes and can aid in the decision-making process for material selection by quantifying the information.

If you’re interested in learning how The Phoenix Group can help your company, contact us today.